Climate Models

Nordhaus’ Modelling

From Blair Fix:

The conflation of income with productivity has led economists to misunderstand the role of natural resources in human societies. Economists see that the owners of natural resources earn a trivial share of income. And so they conclude (wrongly) that natural resources themselves play a trivial role in the economy. It’s an embarrassing mistake with troubling consequences.

Take, as an example, the need to fight climate change. If you ask a climate scientist, they’ll likely say that climate change poses a dire threat to humanity. Their reasoning is simple. Climate change could potentially make farming impossible in much of the world. So if we want to avoid mass starvation, we’d best curb our fossil fuel habit.

In contrast, if you ask a neoclassical economist about fighting climate change, you’ll get a very different answer. Climate change, they’ll likely say, isn’t much of a problem. True, it may cause much of our arable land to become barren … but don’t worry. Agriculture, they’ll observe, is a tiny part of GDP. So even if we destroy our ability to farm, ‘economic output’ will remain virtually unchanged.

Given its absurdity, you might think that I’m making this reasoning up. But I’m not. William Nordhaus — whose work on the economics of climate change has been enormously influential — uses the same reasoning to downplay the impact of global warming. Here’s how he peddles it:

T]he process of economic development and technological change tend progressively to reduce climate sensitivity as the share of agriculture in output and employment declines and as capital-intensive space heating and cooling, enclosed shopping malls, artificial snow, and accurate weather or hurricane forecasting reduces the vulnerability of economic activity to weather … More generally, underground mining, most services, communications, and manufacturing are sectors likely to be largely unaffected by climate change—sectors that comprise around 85 percent of GDP.

Although climate change may destroy our food supply, we shouldn’t worry. According to Nordhaus, we’ll all be safe inside our air-conditioned offices, with productivity unimpaired.

There’s a fatal flaw in this thinking. The decline in agriculture’s income share says nothing about agriculture’s biophysical importance. To see the biophysical importance of agriculture, we should look not at the income-accounting table, but at the kitchen table. No agriculture … means no food … means no humans.

Far from indicating agriculture’s irrelevance, the evidence shows agriculture’s continued importance. Industrial society is possible only because so few people are needed to grow food. (That’s why farmers earn such a tiny share of all income. There are hardly any of them!) Modern farmers harvest a staggering quantity of food. This allows the rest of us to do the non-farming activities that we take for granted. Without the bounty of modern agriculture, urban life would be impossible.

Blair Fix (2020) World without Natural Resources?

Climate economics Nobel may do more harm than good

“Nordhaus’ DICE model implicitly assumes that climate damages are worse when we are richer, and that we should start low and increase the price of carbon over time,” said Wagner. “But what if climate change makes us poorer every step of the way?”

There are by now dozens of economic studies, he pointed out, showing how global warming is already hitting growth rates and productivity.

“We don’t argue against DICE’s conclusions with the force of an ethical argument, we offer a new model that calculates a price of CO2 by taking the financial economic view seriously,” Wagner added.

“And that price is not the 20, 30 or 40 dollar that Bill comes up with. In our model, we can’t get our price below 120 a tonne.”

Hood on Nordhaus vs. Weitzman/Wagner

Reclibrating DICE

Nordhaus finds that 3.5C waring in 2100 is ‘optimal’ - so that we can just skip trying to stay within the IPCC recommended 1.5C. This is du to his discounting of the future - and his presumption that economic growth will contunue as fast as it has - so that future generations will be much more affluent than we and thus more easily can ‘pay’ for damges and reparations.

DICE has also been criticized on several grounds.These include the choice of discounting parameters, the model’s omission of uncertainty and the risk for climate catastrophes, the treatment of non-market damages and details of its climate model. Notably the DICE model’s concept of economic optimality, that is maximizing a discounted utilitarian social welfare function, has been criticized for not reflecting the structure of optimal-control models that incorporate risk and uncertainty and for its reliance on a single conception of intergenerational welfare. DICE has also been subject to general criticism regarding the use of cost–benefit analysis for climate policy purposes

However, recent research on improved versions of Nordhaus’ DICE model suggests otherwise:

Hänsel 2020 Climate economics support for the UN climate targets

CMIP6

Long Term Modelling - Short Term Testing?

ECS - Equilibrium Climate Sensitivity

ECS translates a doubling of atmospheric CO2 concentrations into eventual global average temperature rise. It has been persistently difficult to pin ECS down in that ‘likely’ estimates for decades have ranged from 1.5 C to 4.5 C per doubling of CO2.

SCC - Social Cost of Carbon SCC

Although precise definitions vary, the goal of the SCC is to quantify the tradeoffs between the benefits and costs of cutting CO 2 emissions and to capture them in a single number: the price that society pays for emitting a marginal ton of CO2 The SCC is also the price that each of us should pay for emitting an additional ton. The SCC is important for designing policies such as carbon prices. More broadly, the SCC summarizes the ur- gency of dealing with climate change. A low SCC would be grounds for delaying transformative changes to our energy infrastructure. A high SCC, meanwhile, in- dicates that we will pay dearly for not acting decisively now.

The SCC is highly sensitive to uncertainty in both climate and weather extremes. Both extreme climate change and extreme weather, in turn, lead the most current SCC estimates to be biased toward lower values, often significantly so. By underestimating the SCC, we are underestimating the need for drastic climate action.

On the cost side, most climate-economy models fail to account for how technological progress and the deployment of new low-carbon technolo- gies depend on investment over time

Calculating the benefits of cut- ting CO 2 emissions—or, conversely, the costs of unmitigated climate change—in- volves two main steps: one physical and one economic. The first links the marginal ton of emitted CO 2 to the resulting warm- ing, and the second links it to the resulting economic impacts. Both the magnitude and damages of future climate change are beset with significant and recalcitrant uncertainties, 5 translating into large un- certainties in the SCC. As a result, the SCC is often presented as a draw of out- comes from a simulation exercise that generates a distribution of possible out- comes around a particular median or cen- tral estimate.

Because damages are generally represented as a function of overall warm- ing and often rely on global approxima- tions for damages, there is no direct ac- counting for changes in extreme events.

Even small changes in mean warming can lead to large changes in the probability of extreme temperatures, which in turn can have devastating conse- quences. Because economic damages are particularly large for extreme events, any such increase in their intensity will have an outsized impact on the SCC.

Many of the known processes that are poorly quantified, such as effects from clouds, have signifi- cantly more potential to amplify rather than dampen warming.

The world is riding the complex climate system into a state for which there is no good analog in over a million years. This makes forecasting climate change a fundamentally tricky out-of-sample prediction problem. Surprises are sure to exist, and if they could be quantified, they would also primarily push the SCC to- ward higher values.

There is a lot of room on the extreme warming tail of ECS, whereas values of ECS lower than about 1 C can be ruled out given that global average temperatures have already risen by as much, even though CO 2 has yet to double from pre-industrial levels. This skews un- certainties in long-term physical climate impacts toward higher rather than lower temperatures.

The more fundamental reason for why unknown unknowns should increase the SCC are ever-present threshold effects. Even symmetric uncertainty in how extreme events will change nonetheless leads to potentially large increases in climate damages and thus the SCC.

Uncertainty in the consequences of climate change has often been advocated as a reason to delay action. “We don’t yet know for sure,” the argument goes, “so we better wait and see and do more research”. Quite the contrary. As our knowledge advances, it is much more likely that the true SCC will reveal it- self to be larger than current estimates. It is precisely the uncertainties that make climate change so costly.

Proistosescu and Wagner (2020) Uncertainties increase Social Cost of Carbon pdf

Extreme Event Attribution

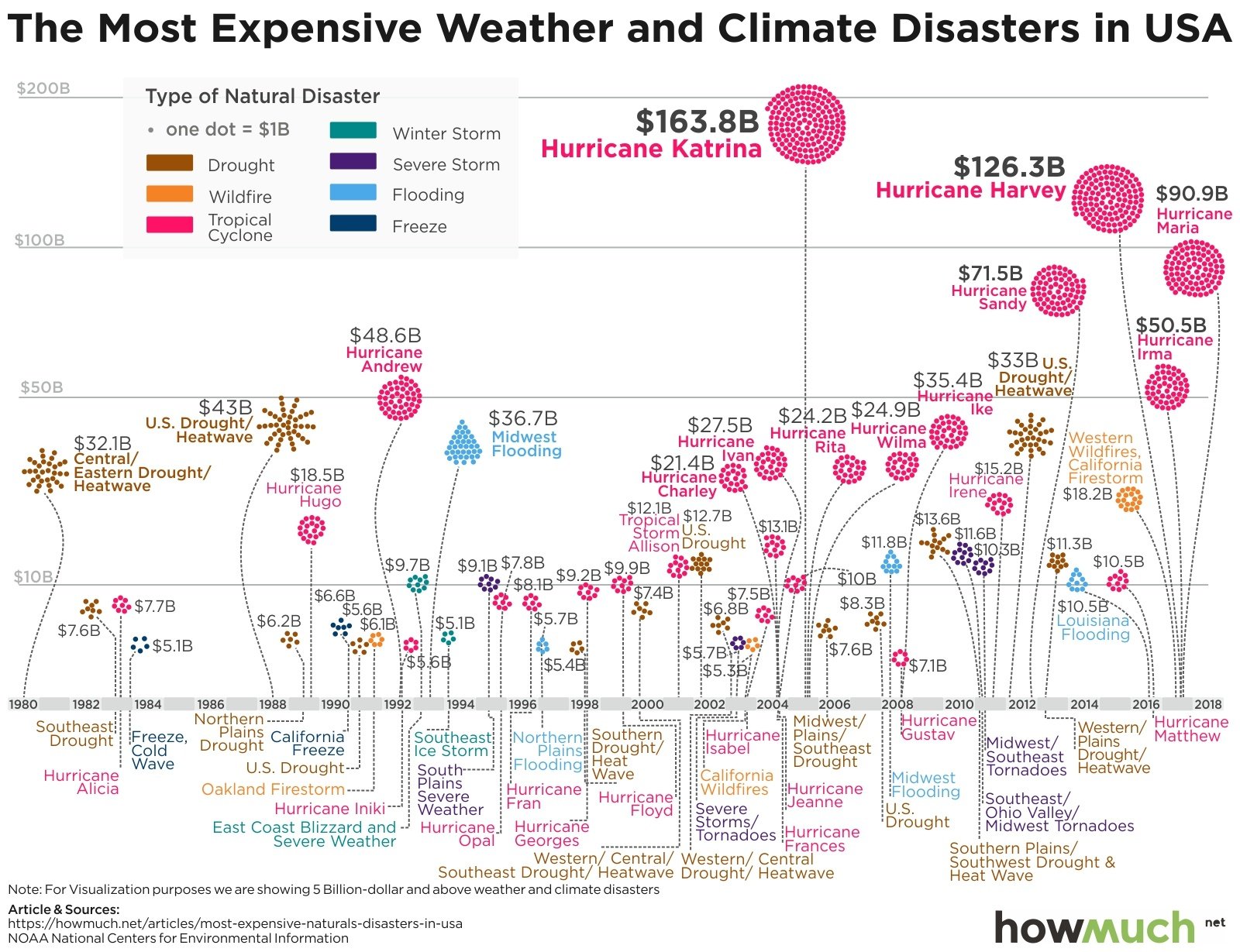

Since 1980 the top five most expensive events were all hurricanes and all took place in the last six years

How can we be confident human greenhouse gas emissions causes this development?

AMS Explaining Extreme Events from a Climate Perspective

CarbonBrief Costs of extreme wheather severely underestimated

Frame (2020) Climate change attribution - rainfall and drought (pdf)

NOAA (2016) Human-caused intensification of 2015 heat waves