14 Decoupling

Hausfather

Absolute Decoupling of Economic Growth and Emissions in 32 Countries

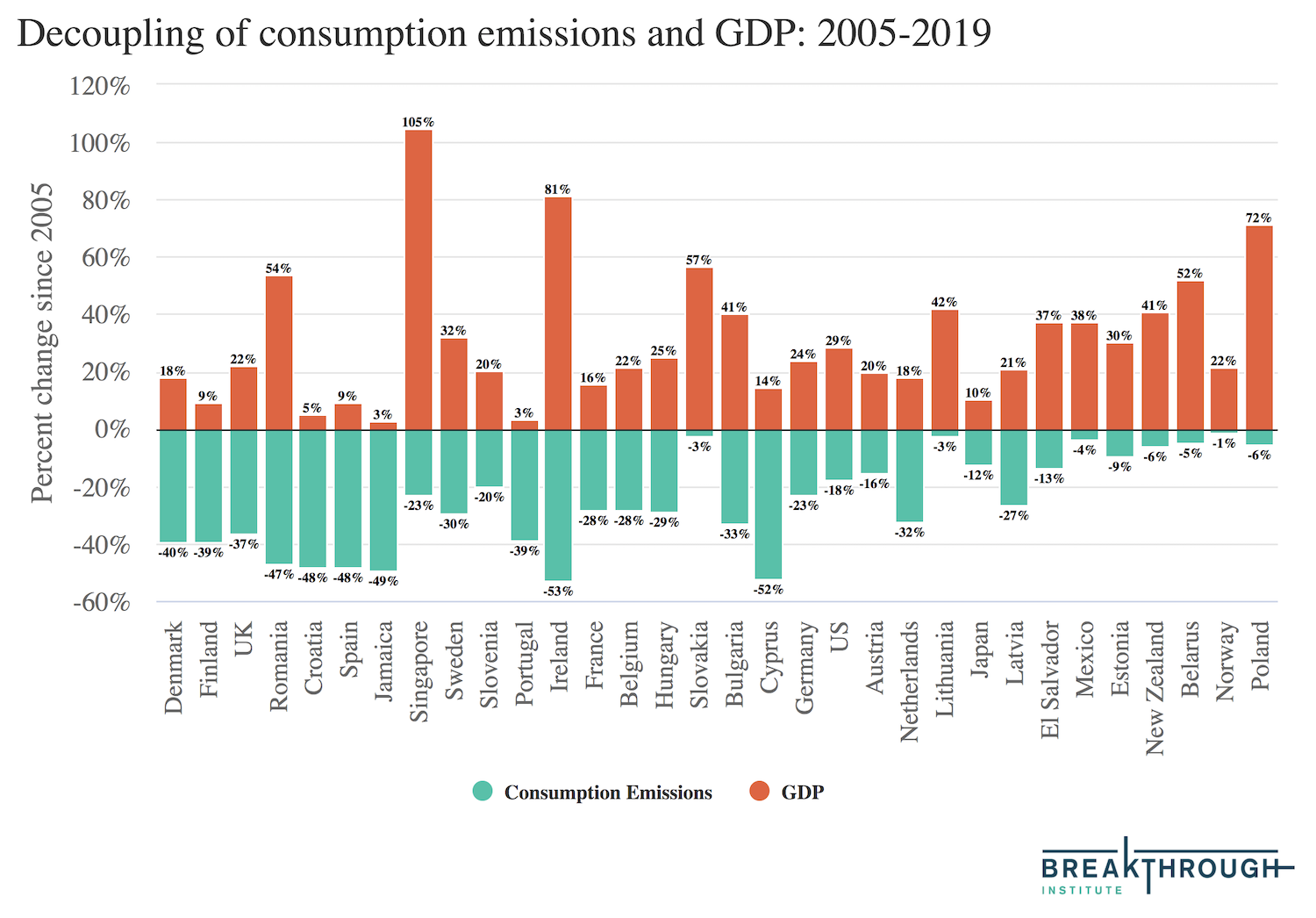

Between 1990 and 2019, global emissions of CO2 increased by 56%. Historically, economic growth has been closely linked to increased energy consumption — and increased CO2 emissions in particular — leading some to argue that a more prosperous world is one that necessarily has more impacts on our natural environment and climate. There is a lively academic debate about our ability to “absolutely decouple” emissions and growth — that is, the extent to which the adoption of clean energy technology can allow emissions to decline while economic growth continues.

Over the past 15 years, however, something has begun to change. Rather than a 21st century dominated by coal that energy modelers foresaw, global coal use peaked in 2013 and is now in structural decline.

These 32 countries show that it is possible to have economic growth at the same time that CO2 emissions decline, even accounting for embodied emissions in goods imported from overseas. However, these are mostly relatively wealthy countries whose economies tend to be increasingly driven by lower-energy information technology and service sectors. We have relatively few examples of low- or middle-income countries with a focus on energy-intensive manufacturing experiencing absolute decoupling to date.

Absolute decoupling is possible. There is no physical law requiring economic growth — and broader increases in human wellbeing — to necessarily be linked to CO2 emissions. All of the services that we rely on today that emit fossil fuels — electricity, transportation, heating, food — can in principle be replaced by near-zero carbon alternatives, though these are more mature in some sectors (electricity, transportation, buildings) than in others (industrial processes, agriculture).

Hubacek Abstract

Decoupling economic growth from resource use and emissions is a precondition to stay within planetary bound- aries. A number of countries have achieved a reduction in their production-based emissions in the past decade. However, the decline in PBE has often been achieved via outsourcing of emissions to other countries, which may even lead to higher emissions globally. Therefore, a consumption-based perspective that accounts for a country’s emissions along global supply chains should also be employed when investigating progress in decoupling. Here we investigate the progress countries made in reducing their production-based and consumption-based emissions despite growth in gross domestic product (GDP). We found that 32 out of 116 countries (mainly developed ones) achieved absolute decoupling between GDP and production-based emissions in recent years (2015–2018), and 23 countries achieved absolute decoupling between GDP and consumption-based emissions. 14 countries have de- coupled GDP growth from both production- and consumption-based emissions. Even countries that have achieved absolute decoupling are still adding emissions to the atmosphere thus showing the limits of ‘green growth’ and the growth paradigm. We also observed that decoupling can be temporary, and decoupled countries may switch back to increasing emissions, which means that continuous efforts are needed to maintain decoupling. An analysis of driving factors shows that whether a country can achieve decoupling mainly depends on reducing emission intensity along domestic and import supply chains. This highlights the importance of decarbonizing supply chains and international collaboration in controlling emissions.

Hubacek Conclusion

The results show that 32 countries (mainly developed ones) have ab- solute decoupling between GDP and production-based emissions in re- cent years (2015–2018). However, the decline in PBE could have been achieved via outsourcing of emissions to other countries. Our analy- sis shows that only 23 countries achieved absolute decoupling between GDP and consumption-based emissions. Another 67 countries (or 58%) have relatively decoupled, and 19 (or 16%) coupled economic growth with CBE. 6 countries were in an economic recession during the study period. We also observed that decoupling can be temporary, and decou- pled countries may switch back to increasing emissions, which means that continuous efforts are needed to maintain decoupling. An analysis of driving factors shows that whether a country can achieve decoupling mainly depends on reducing emission intensity along domestic and im- port supply chains. This highlights the importance of decarbonizing sup- ply chains and international collaboration in controlling emissions. While there have been some achievements in decarbonizing global value chains these have been by far not sufficient as overall global emis- sions have continued to rise. Even though some countries have achieved absolute decoupling, they are still adding emissions to the atmosphere thus showing the limits of ‘green growth’ and the growth paradigm. Even if all countries decouple in absolute terms, this might still not be sufficient to avert dangerous climate change. Therfore, decoupling can only serve as one of the indicators and steps toward fully decarbonizing the economy and society.