The Symbiosis between Market and State

Under the title ‘The fourth power?’ Wolfgang Streeck in New Left Review 110, March-April 2018 makes a review of Joseph Vogl: The Ascendancy of Finance (2017), first published in German as Der Souverãnitãtseffekt (2015) Here we find a lot of interesting characterizations of Current Capitalism. Below follows some extracts.

In fact, according to Vogl, states became sovereign by co-opting finance into their emerging sovereignty and parcelling out part of that sovereignty to the markets, thereby creating a private enclave within public authority endowed with a sovereignty of its own. Just as modern society could not have been monetized without state authority, so the state could only become society’s executive committee by making finance the executive committee of the state. Money, then, emerges in what Vogl calls ‘zones of indeterminacy’, where private and public interests are reconciled by assigning public status to the former and privatizing the latter. The result is a complex interlocking of conflict and cooperation generative of, and benefiting from, what Vogl calls ‘seigniorial power’—a relationship in which the state and finance undertake to govern one another and, together, society at large.

It is in crisis situations, when banks are about to collapse or states teeter on the edge of insolvency, that the liberal notion of a clear distinction between markets and the state is exposed as a myth. On such occasions, as financial and political elites join forces in a virtual boardroom, func- tional differentiation—the pet category of functionalist sociology—loses its meaning and sovereignty reveals a Schmittian face, declaring a state of emergency and die Stunde der Exekutive. As Vogl shows in his account of the Wall Street ‘rescue operation’ of autumn 2008, in the hour of the executive, huge public funds suddenly become available to exclusive circles of bankers and their presumptive overseers. Working together as the clock ticks, they take command decisions whose consequences nobody can pre- dict, in an effort to maintain at least the appearance of control over events, and to prevent the pyramid of promises that is financialized capitalism from collapsing under the weight of mounting suspicion that it might have become unmanageable.

In calmer times, the two poles of seigniorial power—the state and the market—meet and merge in the central bank, the hybrid institutional core of capitalism’s ‘zone of indeterminacy’…. What distinguishes them as a type is that they exist to protect finance from the fickleness of political rulers—absolutist or democratic—while providing the latter with at least the illusion of control over the fickleness of financial markets. Institutional independence is cru- cial, nowadays meaning above all insulation from electoral politics. Monetary questions must be de-politicized—which is to say, de-democratized. Central banks, Vogl argues, constitute a fourth power, overshadowing legislature, executive and judiciary, and integrating financial-market mechanisms into the practice of government.

Rising political-economic volatility implies a loss of power for Vogl’s cen- tral banks, and a loss of respect as well. In July 2017, a year after its embrace of radical uncertainty, the same investment house explained to its clients why interest rates were, and would remain, so low. Central banks do not figure in the story at all. Instead the culprit is the ‘superstar firm’, its rise made pos- sible by new technology and globalized markets. To quote: ‘superstar firms make higher profits, save more than they invest and pay out a smaller share of their value-added to labour.’ This explains ‘key macro phenomena such as the global ex ante excess of saving over investment, rising income and wealth inequality, and low wage inflation despite falling unemployment, all of which has contributed to the current environment of low natural and actual interest rates, which in turn supports high valuations for the superstars.’ In this ‘winner takes most’ world, economic concentration is increasing. Large firms sit on huge cash hoards while labour’s income share declines. High wages for the privileged few employed by superstar firms, combined with weak wage pressure in an increasingly fragmented low-wage sector, make for worsening inequality, adding to the global savings glut as ‘high-income, wealthy individuals have a higher propensity to save than low-income, less wealthy ones’—an account remarkable for its similarity with standard ‘radi- cal’ explanations of the crisis of contemporary capitalism. Together, these dynamics keep inflation down even if central banks want prices to go up. Therefore, the experts say, ‘the investment strategy of choice’ must be one calibrated to a ‘long-term low interest-rate environment’.

In a final chapter titled ‘Reserves of Sovereignty’, Vogl deals with the submersion of nationally organized financial sectors—rendered politi- cally unmanageable by financial innovation and the internationalization of capital—into an emerging global regime. Here again, Vogl’s command of his conceptual apparatus enables him to make sense of a highly complex process, conceived as yet another permutation of the relationship between the public and the private, and amounting to the conversion of ‘regulation’ into ‘governance’—in particular, ‘global governance’. Financialization for Vogl essentially involves the transfer of financial oversight to the financial markets themselves, ultimately establishing oversight of states by markets. Subjected to the dictates of capital accumulation, the relations that make up the infrastructure of social life are financialized, depoliticized and indeed de-socialized. Responsibility for economic order shifts from constitutional, potentially democratic, governments to ‘a patchwork of public entities, international organizations, treaties and private actors which superintends the privatization of regulation and, as a consequence, the marketization and informalization of law and legal institutions’. As governance is privat- ized, finance becomes the sole remaining sovereign.

…it might have been worth his while to place the evolving relalionship between public spending, public debt, taxation and interest, and the public-choice rhetoric surrounding this, in a larger political-economic context transcending institutional analysis proper. What if the pressure for ever-higher public spending was a reflection, not of democratic ‘irrespon- sibility’, but of what in Marxian language would be described as a secular tendency toward the ‘socialization of production’, giving rise to a functional need for private profit-making to be supported by an increasingly elaborate, and correspondingly more expensive, public infrastructure? It is here that Vogl’s institutional analysis of the bipolar world of his zone of indetermi- nacy might have benefitted from being embedded in a political economy of contemporary capitalism, a context in which it would greatly contribute to our understanding of a, shall we say, dialectical ‘contradiction’ between the limited supply of tax revenue on the one hand—caused by capital’s reluctance to be taxed—and on the other, the growing demands, including capitalist demands, for public prepare-and-repair work, from education to environmental clean-up; for public security, from citizen surveillance in the centre to anti-insurgency on the periphery; and for public compensation of citizens for loss of income and status due to capitalist creative destruction.

…states must be willing and able to service and repay their debt reliably, and it is here that central banks still seem to play an important role in the management of ‘financia- lized’ capitalism. Not only can they mediate between states and the financial industry—bankrolling the former and allowing the latter to trade govern- ment debt for profit—they also help to keep public debt at a level where states can still be trusted by their private creditors.

So far Streeck/Vogl. Today The Guardian has a article on the replacement of Mark Carney as head of Bank of England - foreseen to come just after Brexit comes into effect. Carney is charcterized this way: … one of the few senior policymakers taking measured decisions in the national interest rather than the narrow party interest that dominates parliament. So it’s a tall order finding a replacement.

Parliamentary democracy seems to be lost in a cul-de-sac. Luckily we can count on the New Enlightened Rulers of the Central Banks.

Yanis Varoufakis adds a different twist to this analysis in his comment on Project Syndicat in August 2018:

Austerity prevails in the West because three powerful political tribes champion it. Enemies of big government have coalesced with European social democrats and tax-cutting US Republicans, to create a cartel-based, hierarchical, financialized global economic system.

…capitalism has been evolving. The vast majority of economic decisions have long ceased to be shaped by market forces and are now taken within a strictly hierarchical, though fairly loose, hyper-cartel of global corporations. Its managers fix prices, determine quantities, manage expectations, manufacture desires, and collude with politicians to fashion pseudo-markets that subsidize their services….

…as the hyper-cartel became financialized (turning companies like General Motors into large speculative financial corporations that also made some cars), the aim of GDP growth was replaced with that of “financial resilience”: ceaseless paper asset inflation for the few and permanent austerity for the many…

…an overarching dynamic that, under the guise of free-market capitalism, is creating a cartel-based, hierarchical, financialized global economic system.

From a review of Vogl’s book by James McRitchie:

The Ascendancy of Finance presents a convincing explanation of a major threat, not only to democracy but to the individual’s freedom to live a meaningful existence, instead of as an economic robot. Like Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Vogl offers little in the way of recommendations for how to deal with the monster we have unleashed. Shelly warned against ambition as the Creature morned his creator’s death and vanished onto the ice in an act of self-sacrifice. Our creation is much further along and is unlikely to follow suit.

Globalization

International Imbalances

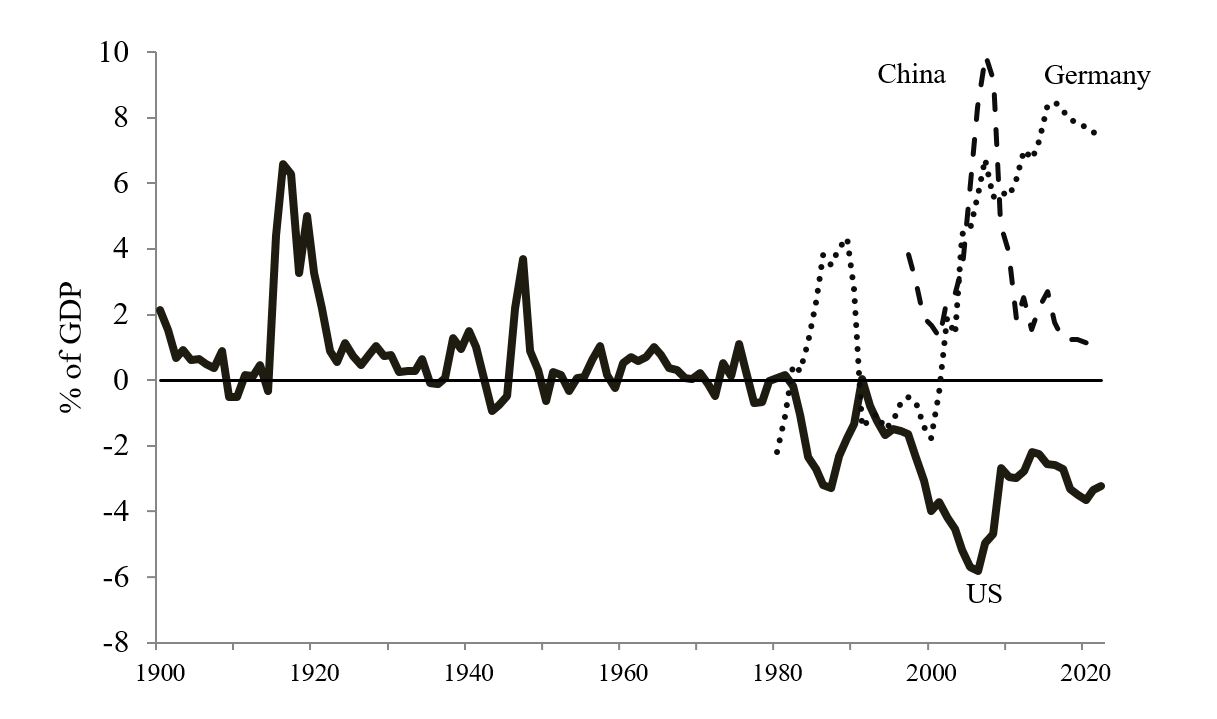

Current Account Balances, Actual and Forecast (2017-2022): US, China, and Germany (% of GDP)

Sources: Historical Statistics of the United States, Economic Report of the President, IMF World Economic Outlook. (Carmen Reinhardt)

Nationalism

The appearance of a Catalan state would be only another facet of a slow dismantling process emerging all over the world, pushed forward – surprisingly – by globalisation.

Monetary Policy

Who creates Money/Debt?

The lost lesson of the 2007 financial crisis is that current economic-growth models are “overly reliant on liquidity and leverage – from private financial institutions, and then from central banks.”(Mohamed El-Erian). Financial markets’ performance today is driven by the expectation of continued central-bank liquidity.

Derivatives markets created a system of largely fraudulent circular insurance that allows bankers to raid their bank capitals and pay it out to themselves and select shareholders as bonus. What this amounts to practically is a license to print counterfeit money through fraudulent credit. Fraudulent credit can be defined as credit that is designed at origination to be impossible or highly unlikely to be repaid. (Mirek Fatyga)

With the rise of financialization, commercial banks have become increasingly reliant on one another for short-term loans, mostly backed by government bonds, to finance their daily operations. This liquidity acquires familiar properties: used as a means of exchange and as a store of value, it becomes a form of money. And there’s the rub: as banks issue more inter-bank money, the financial system requires more government bonds to back the increase. The growing inter-bank money supply fuels demand for government debt, in a never-ending cycle that generates tides of liquidity over which central banks have little control. In this brave new financial world, central banks’ independence is becoming meaningless, because the money they create represents a shrinking share of the total money supply. With the rise of inter-bank money, backed mostly by government debt, fiscal policy has become an essential factor in determining the quantity of actual money lubricating modern capitalism. Indeed, the more independent a central bank is, the greater the role of fiscal policy in determining the quantity of money in an economy. Money and government debt are now so intertwined that the analytical basis for central bank autonomy has disappeared. (Yanis Varoufakis)

Cryptocurrencies

The market capitalization of cryptocurrencies amounts to nearly one tenth the value of the physical stock of official gold, with the capability to handle significantly larger payment operations, owing to low transaction costs. That means that cryptocurrencies are already systemic in scale. The Central Banks can try to reign in cryptocurrencies but the genie is out of the bottle: the entire model that the combination of governments and Central Banks operate is already under huge threat. Technology basically allows barter to operate on an industrial scale. Technology platforms now open the possibility of direct peer-to-peer transactions, entirely bypassing all banking - retail, merchant and Central. This essentially means the insertion point that governments had into all transactions is lost - which then makes it extremely difficult to extract tax from transactions.