48 Trade

48.1 Absolute Advantage

Welsh

Everyone knows about comparative advantage, but what doesn’t get talked about is absolute advantage. In absolute advantage you have something people need that they can only get from you.

This can be weapons. It can be jets. It can be advanced computers. It can be the capital equipment (like lithography machines used to create semiconductors) used to make other things. Sometimes it can be a resource, like oil.

48.2 Comparative Advantage

Milanovic

Economic dependence is assured through the false doctrine of comparative advantage which, indeed, was not believed by the United States in the period of its rise. Had the Americans followed the principle of comparative advantage they would be exporting furs and bison meat.

Milanovic (2024) Powerful, but within the orbit of the empire

48.3 Supply Lines

Tverberg

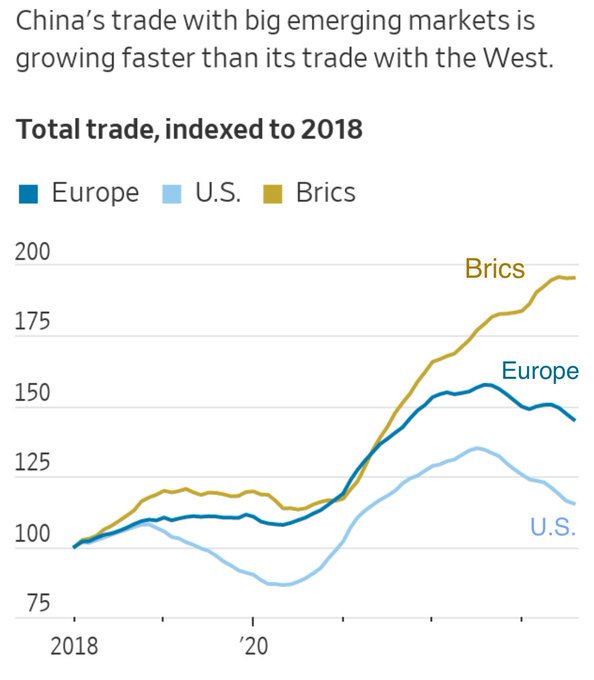

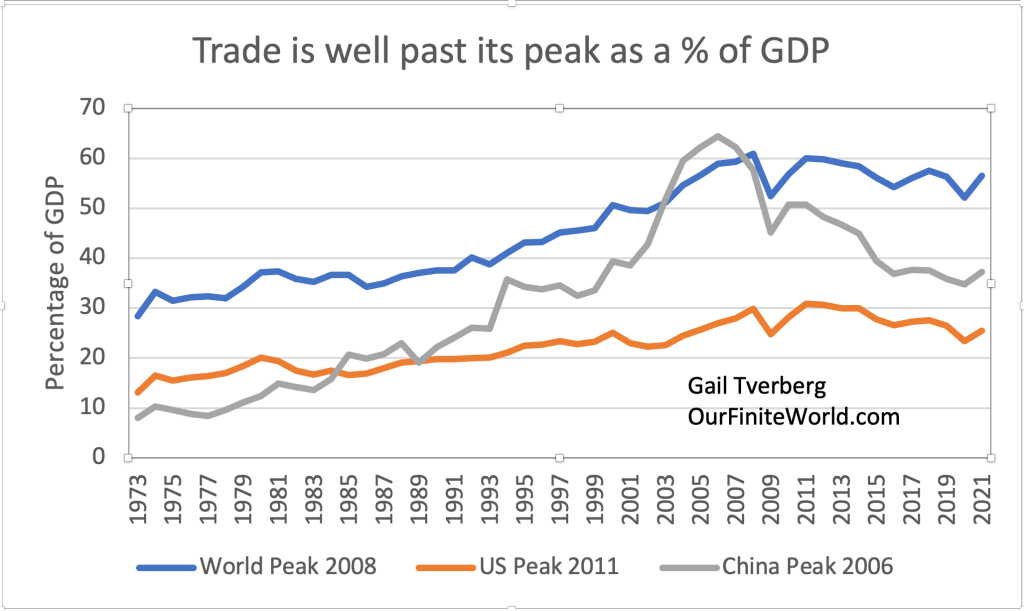

Countries are now actively trying to bring supply lines back closer to home.

Figure: Trade as a percentage of GDP based on World Bank data for the World, the United States, and China.

Tverberg (2023) Today’s energy bottleneck may bring down major governments

48.4 Trading Partners

Welsh

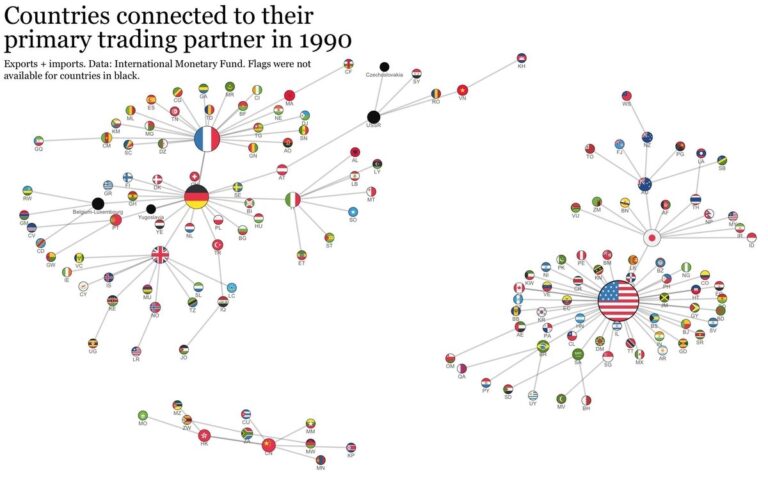

Figure: Trading networks 1990

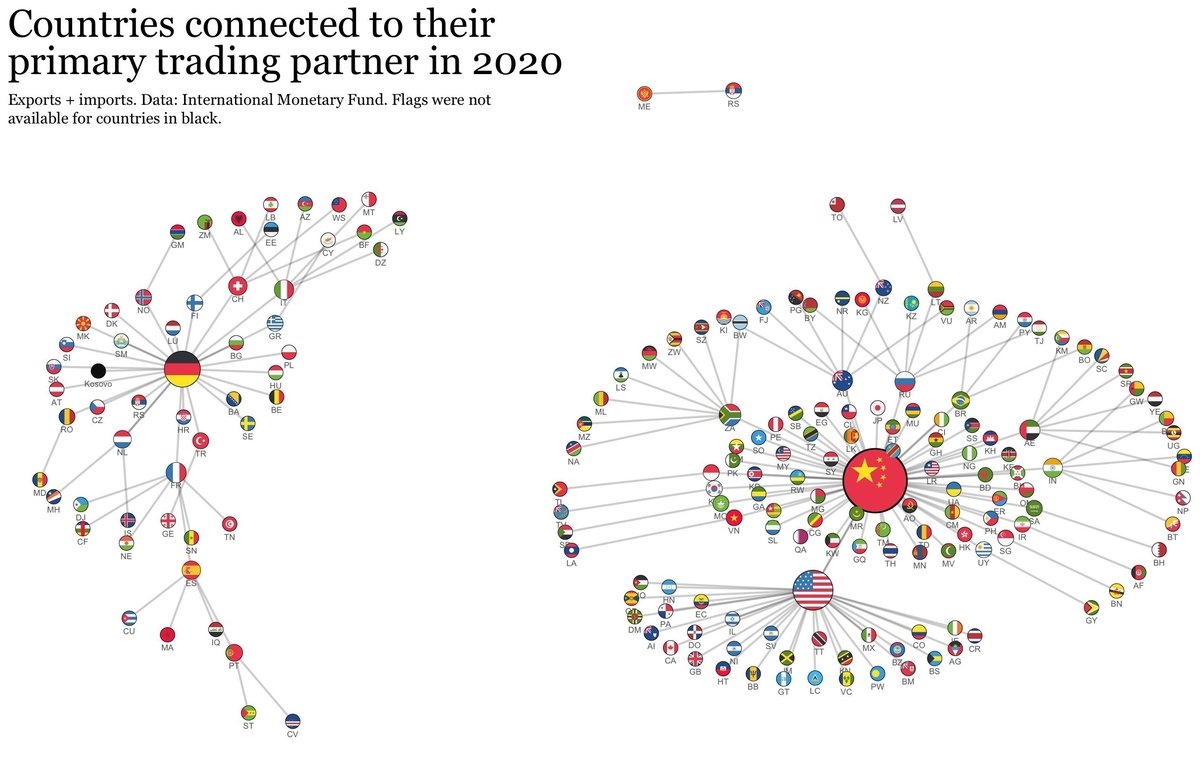

Figure: Trading networks 2020

This sort of thing is a leading indicator. Countries who were dominant are able to control more of the world’s resources than they deserve.

The US has LOST its dominance already. It’s all over except for the shooting. It doesn’t look or feel like that because of generations of accumulation and because the dollar is used for most world trade.

But those are lagging indicators. Britain’s pound was the main instrument of trade for decades after the US had overtaken it industrially.

Since China now offers almost everything the West does, at better terms, they will come to command those resources.

Within the West we are already seeing the US cannibalizing its satrapies.

The main industry the West seems to still have a dominant lead in is biotech, but the Chinese will get there.

Japan and South Korea will do better because both are keeping up in scientific innovation, but my bet is that South Korea will peel off into the Chinese sphere at some point, economically they already have. I’m less sure about Japan, but they’d be wise to do so.

As for Europe, well, for twenty years I’ve been warning them they had to regain their independence and forge their own path. Most of Eastern Europe should never have been allowed into the EU or NATO. The EU should have built its own army and left NATO. And yeah, they should have done everything necessary to keep good ties with Russia, which would have been easy, because until fairly recently Russia wanted to be a European nation.

They did none of this, their rate of scientific advancement is abysmal outside of a few areas and they’re toast.

Welsh (2023) Notes On The Structure Of American Imperial Collapse

48.6 Trade and Savings

Farooqi

Trade imbalances are a mathematical function of relative savings rates. The flipside of current account surpluses are savings outflows. Countries that save more than others must necessarily export their savings; conversely, countries that save less must necessarily import the savings of others. So, the reason for the Chinese trade surplus and American deficit is not Chinese duplicity or that of US firms engaged in outsourcing, but the simple fact that the Chinese savings rate averaged 46 percent since 2000, while the US averaged 17 percent over the same period. The US has a massive trade deficit with Germany for the same reason: Germany’s savings rate has averaged 26 percent since 2000.

There is an even stronger and more obvious reason to believe that trade imbalances are a total red herring when it comes to understanding deindustrialization. Employment in manufacturing has been in secular decline since Woodstock. In 1948-1969, manufacturing employed about 23 percent of the civilian labor force. It has been steadily declining ever since: manufacturing employment averaged 20 percent in the 1970s, 16 percent in the 1980s, 13 percent in the 1990s, 10 percent in the 2000s, and 8 percent in the 2010s. Even if deindustrialization is ultimately responsible for the ‘deaths of despair’ and 2016, import competition from China in the 2000s could not possibly have been responsible because causes must necessarily precede effects.[16] In fact, deindustrialization may itself be a red herring. The structural break for deaths of despair — deaths due to alcohol poisoning, drug overdose and suicide — occurs is the early-1990s.[17] In other words, the structural break occurs decades into the decline of manufacturing and a decade before the China Shock. So, deindustrialization per se cannot be held responsible for the crisis of the American working class either.

48.7 Trade and Productivity

Farooqi

The causal channel through which trade enhances productivity growth has been well understood since Melitz (2003), an academic paper that’s been cited 18,586 times. The Heckscher-Ohlin class of Ricardian models explained inter-industry between countries; they could not be modified to explain the dominant pattern of trade in the core of the world economy: trade within the same industry between countries with similar factor endowments. New trade theory, beginning with the pioneering work of Krugman and Helpman, highlighted the importance of product differentiation and increasing returns to scale to explain why intra-industry trade was dominant and why most trade takes place between countries with very similar factor endowments. Melitz extended the new trade theory to explain the logic of precisely how trade enhances productivity growth. In the modern understanding, trade plays a dynamic role is fostering productivity because exposure to the world market forces the least productive firms to exit and the most productive firms to innovate harder to escape competition. This Schumpeterian logic of creative destruction and the unrelenting disciplinary force of the world market is the key to productivity growth in the advanced industrial core of the modern world economy.

There are two distinct components of intensified import competition that induce adjustments in opposite directions.[27] The first component is vertical: firms using imported intermediate goods and services in their own production processes. The response induced by the vertical component is always positive and works very much like an exogenous productivity shock. All firms that use the more efficient intermediates become more productive and profitable as a result. Market competition then ensures that most of these gains are passed on to consumers in the form of larger consumer surpluses and to workers in the form of higher wages. The second component is horizontal: it affects firms whose products are directly exposed to import competition. For low productivity firms, the horizontal component induces a negative response. Low productivity firms that find it hard to compete with imports lose market share and may be forced to exit. The response of high productivity survivors of the onslaught is usually positive. The intensified discipline of the world market incentivizes the survivors to innovate harder. Both components raise average productivity in the industry.

It may seem that the horizontal component is bad, and the vertical component is good for the home country facing stiffer import competition. But that is a myopic view of the dynamics. By driving the least productive firms to shrink or exit altogether, stiffer import competition frees up factors of production for redeployment towards more productive firms. Financial resources, embodied capital, managerial skill, and above all, the skills and knowhow of the workforce are thereby put to more productive use. This raises aggregate productivity in the industry and for the home country at large. The dynamic welfare gains from Schumpeterian creative destruction are reckoned to be three times larger than the Ricardian gains from trade.

48.8 Scumpeterian Growth Theory

One of the main findings of what’s called Schumpeterian growth theory is of particular importance to the countries of the advanced industrial core. This is the finding that “openness is particularly growth-enhancing in countries that are closer to the technological frontier.”[36] Conversely, tariff walls and non-tariff trade barriers pose special risks for the most advanced economies. Specifically, the risk posed by protectionism is that it would undermine the competitiveness of the center countries.

In terms of trade policy, we must try to reclaim our role as the agenda-setter. This involves shouldering the responsibility of articulating arrangements for the community of nations as a whole. This would require some tolerance of what may look like the loss of strategic sectors. Sheltering incompetent American automakers against Chinese competition is going to make them fatter and less competitive rather than more. At any rate, if we change the rules of the game mid-play because we start losing some valuable pieces, we shall not be able to reclaim our role as the agenda-setter. Trying to prevent China from catching up in computing by garrisoning the world economy is a harebrained idea. It has almost no chance of success. In fact, our chips escalation has already failed. It was designed to prevent Chinese firms from producing chips less than fourteen nanometers thick. They’re already making chips narrower than seven nanometers. We just should let it go. All we can buy with this strangulation plan is the enduring enmity of the Chinese. We can’t actually prevent them from catching up at all. We can only run harder ourselves. That is where the focus of our policies ought to be.