47 Technology Policy

Farooqi

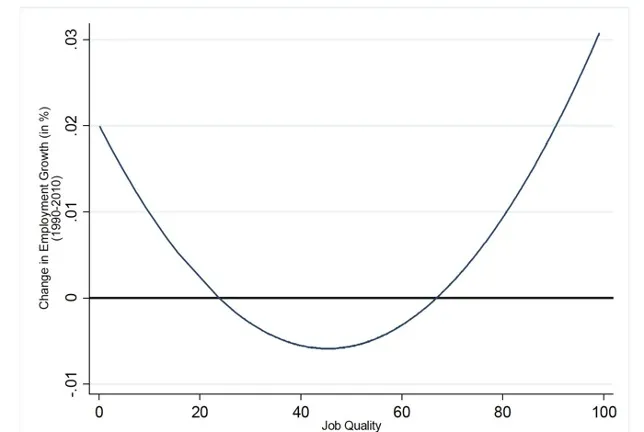

The hourglass occupational structure may be a consequence of the information technology revolution. The technology enabled routinization of production processes of both goods and services. Both men and machines were automated. Machines were automated with code. Workers were automated through routinization of tasks, thereby increasing the scale of operations that could be brought under the precise control of highly-skilled managers. An unanticipated consequence of this development in technics was the vanishing of middle-skilled occupations and the systematic deskilling of the American labor force. As we argued above, this is the correct etiology of the crisis of the American working-class.

The intellectual problem here is the implicit assumption that technology is an exogenous force and not susceptible to policy solutions. This premise is wrong. Technology is endogenous to our institutional arrangements. We can design them to incentivize certain classes of technologies and discourage others, for instance, through favorable or unfavorable tax treatment. A carefully-designed technology policy ought to be one of the pillars of open-ended American developmentalism.

A rather direct form of attack would be to force the pace of the automation of all routine tasks. This would evacuate routine tasks in job task-bundles, thereby reducing the incidence of deskilled jobs. Human workers are great bundles of skill. Using them as automata is a poor use of their human capital. If we can force the pace of automation, we can get rid of deskilled dead-end jobs sooner and reallocate our tremendous human capital towards more productive activities. This policy also works with the grain of technology and markets—the automation of routine tasks in both blue-collar and white-collar occupations is already well underway. The idea that somehow human jobs will vanish due to competition from robots and AI is a luddite fallacy. Automation does not cause aggregate job losses. Rather, automation reconfigures what tasks are bundled together as jobs, increasing their creative content, reducing drudgery, and making them more rewarding for workers.

Policies aimed at reversing occupational polarization will require time to work. Policy formulation and administrative implementation takes time; once there is some clarity over policy, firms will need some time to solve new problems, innovate, and re-bundle jobs; workers will also need time to reskill and master new bundles of responsibilities. So, we’re looking at least a decade long process. We should aim to reskill one hundred million Americans over the next decade. As part of a broader vision of open-ended American developmentalism, we should be constantly refining our strategy to upgrade the skill-set of the American populace—for it is human capital that is the true font of productivity.