8 Taxing

Climate Change Economics

But another approach (draconian taxation) is possible too. Instead of limiting physical quantities of goods and services that fulfill criteria (a) and (b) we would impose extremely heavy taxes on them. There is always a tax rate that would drive consumption of a good down to the level that we have in mind. It is here that I think we can use—again if we believe that the climate emergency is so dire—the lessons of covid.

Economic dislocations would be huge. It is not only the question of the entire upper middle class and the rich in advanced countries (and, as we have seen, elsewhere) losing significant parts of their real income as prices of most “staple” commodities (for them) increase by two, three or ten times; the dislocation will affect large sectors of the economy.

The effects will trickle down: unemployment will increase, incomes will plummet, the West will record the largest real income decline since the Great Depression.

However if such policies were steadfastly pursued for a decade or two, not only would emissions plummet too (as they have done in 2020), but our behavior and ultimately the economy would adjust. People will find jobs in different activities that will remain untaxed and thus relatively cheaper and whose demand will go up. Revenues collected from taxing “bad” actvities may be used to subsidize “good” activities or retrain people who have lost their jobs.

This is not magical thinking. These are policies that, with intergovernmental cooperation, knowledge of economics, data on global inequality, and the experience of covid, could be implemented.

8.1 Tax Shifting

FT

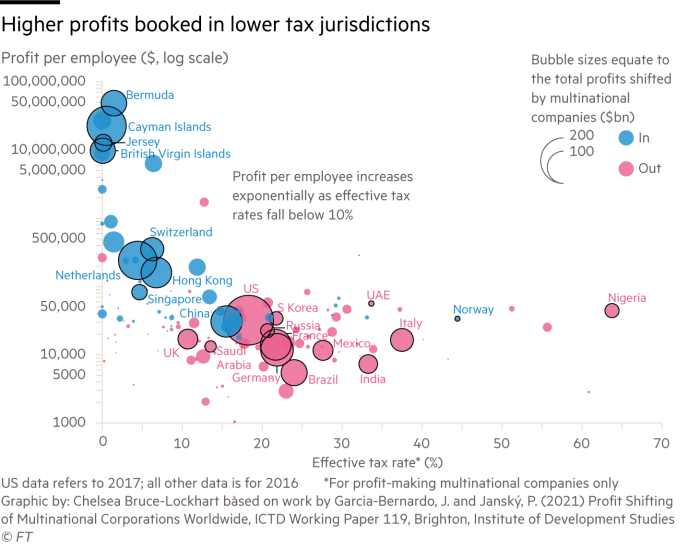

US president Joe Biden’s plan to reform global corporate taxation will do little to help the countries most inneed of more tax revenues, say developing economies which are lobbying for greater power over multinationals.

Washington’s ambitious proposal would tax 100 of the world’s largest companies on profits made in countries where they have little or no physical presence but derive substantial revenues and would introduce a global minimum tax rate, in a bid to end what it dubbed a “race to the bottom” where businesses channel profits through low-tax jurisdictions.

But companies would pay most of their taxes in the country where they are headquartered, even if their profits — and in many cases the labour and raw materials used — are sourced from developing countries, senior diplomats and lobby groups told the Financial Times.

They are also concerned that many developing countries are not participating in the negotiations over the proposal at the OECD and fear the eventual agreement is unlikely to reflect their interests.

8.2 Georgism - Land Value Tax

Doucet

Georgism is a school of political economy that is really upset about, among other things, the Rent Being Too Damn High. It seeks to liberate labor and capital alike from those who gatekeep access to scarce “non-produced assets,” such as land and natural resources, while still affirming the virtues of hard work and free enterprise. George uses the term “Land” to mean not just regular land, but everything that is external to human beings and the things they produce–nature itself, really.

Georgism’s chief insight is to move economic thinking from a two-factor model (Labor and Capital) to a three-factor model (Land, Labor, and Capital). It’s chief (but not only) policy prescription is the Land Value Tax (LVT), which taxes real estate at as close to 100% of its “land rent” as possible (the amount of rent due to the land alone apart from “improvements” such as buildings). In actual practice, most Georgists seem to think 85% is a reasonable figure to target.

Lars Doucet (2022) Does Georgism Work? Part 1: Is Land Really A Big Deal?