5 The Human Niche

Xu

Significance We show that for thousands of years, humans have concentrated in a surprisingly narrow subset of Earth’s available climates, characterized by mean annual temperatures around ∼13 °C. This distribution likely reflects a human temperature niche related to fundamental constraints. We demonstrate that depending on scenarios of population growth and warming, over the coming 50 y, 1 to 3 billion people are projected to be left outside the climate conditions that have served humanity well over the past 6,000 y. Absent climate mitigation or migration, a substantial part of humanity will be exposed to mean annual temperatures warmer than nearly anywhere today.

Abstract

All species have an environmental niche, and despite technological advances, humans are unlikely to be an exception. Here, we demonstrate that for millennia, human populations have resided in the same narrow part of the climatic envelope available on the globe, characterized by a major mode around ∼11 °C to 15 °C mean annual temperature (MAT). Supporting the fundamental nature of this temperature niche, current production of crops and livestock is largely limited to the same conditions, and the same optimum has been found for agricultural and nonagricultural economic output of countries through analyses of year-to-year variation. We show that in a business-as-usual climate change scenario, the geographical position of this temperature niche is projected to shift more over the coming 50 y than it has moved since 6000 BP. Populations will not simply track the shifting climate, as adaptation in situ may address some of the challenges, and many other factors affect decisions to migrate. Nevertheless, in the absence of migration, one third of the global population is projected to experience a MAT >29 °C currently found in only 0.8% of the Earth’s land surface, mostly concentrated in the Sahara. As the potentially most affected regions are among the poorest in the world, where adaptive capacity is low, enhancing human development in those areas should be a priority alongside climate mitigation.

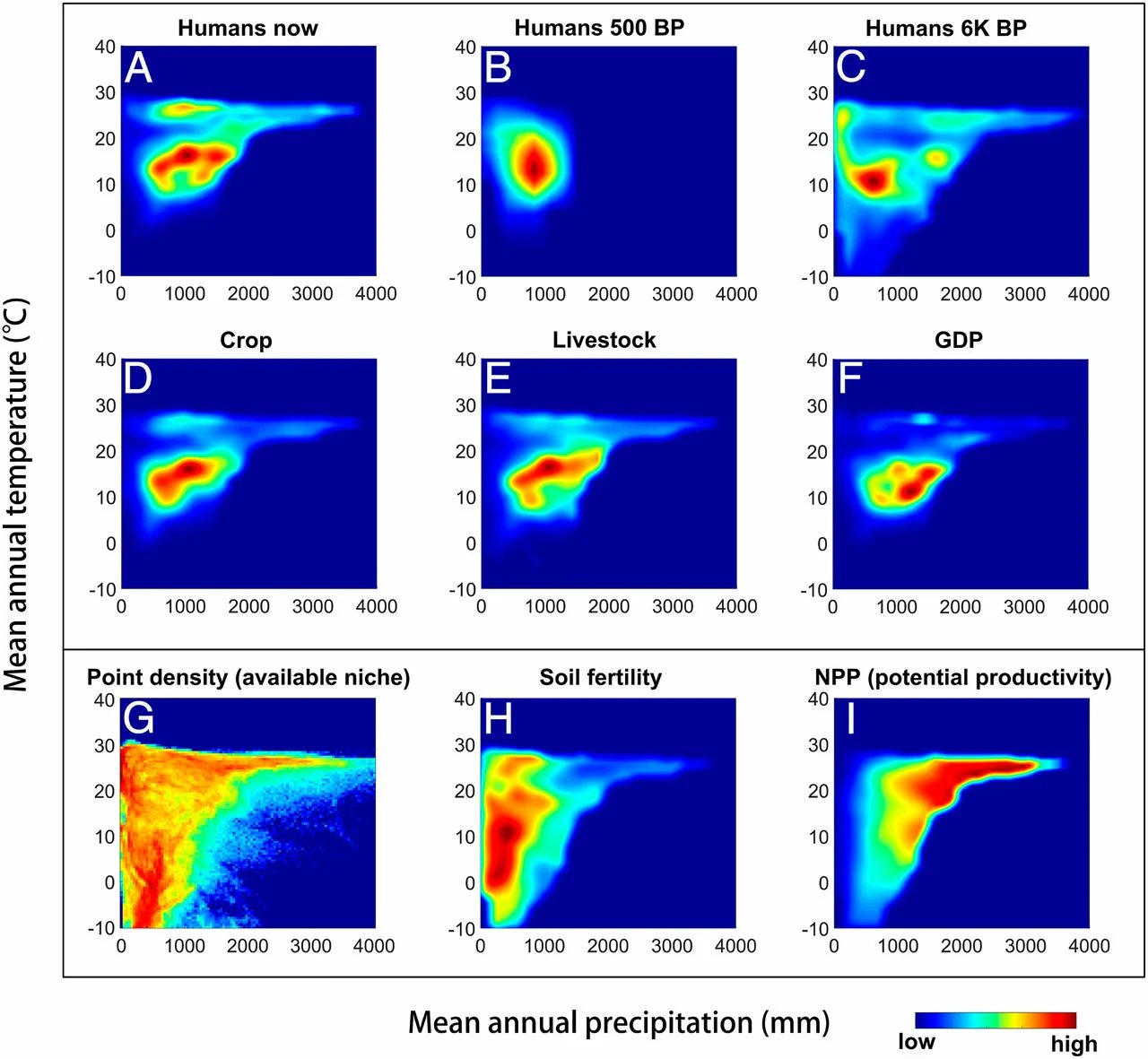

Figure: The realized human climate niche relative to available combinations of MAT and precipitation. Human populations have historically remained concentrated in a narrow subset (A–C) of the available climatic range (G), which is not explained by soil fertility (H) or potential primary productivity (I). Current production of crops (D) and livestock (E) are largely congruent with the human distribution, whereas gross domestic product peaks at somewhat lower temperatures.

Humans, as well as the production of crops and livestock are concentrated in a strikingly narrow part of the total available climate space. This is especially true with respect to the mean annual temperature (MAT), where the main mode occurs around ∼11 °C to 15 °C.

Much of range of precipitation available around that temperature is used, except for the driest end.

Soil fertility does not seem to be a major driver of human distribution, nor can potential productivity be a dominant factor, as net primary productivity shows a quite different geographical distribution, peaking in tropical rainforests, which have not been the main foci of human settlement.

The apparent conditions for human thriving have remained mostly the same from the mid-Holocene until now.

As far back as 6000 y BP, humans were concentrated in roughly the same subset of the globally available temperature conditions.

Explaining such patterns of economic dominance requires unraveling the dynamics of historical, cultural, and institutional settings, which is beyond the scope of this paper.

The precipitation niche turns out to have broadened over the past centuries, leaving only the driest part of the gradient unoccupied.

The human population distribution in relation to MAT has remained largely unaltered, with a major mode around ∼11 °C to 15 °C accompanied by a smaller secondary mode around ∼20 °C to 25 °C corresponding largely to the Indian Monsoon region.

The historical inertia of the human distribution with respect to temperature contrasts sharply to the shift projected to be experienced by human populations in the next half century.

Absent climate mitigation or human migration, the temperature experienced by an average human is projected to change more in the coming decades than it has over the past six millennia.

Compared with the preindustrial situation 300 y BP, the mean human-experienced temperature rise by 2070 will amount to an estimated 7.5 °C, about 2.3 times the mean global temperature rise, a discrepancy that is largely due to the fact that the land will warm much faster than the oceans, but also amplified somewhat by the fact that population growth is projected to be predominantly in hotter places

Over the coming decades, the human climate niche is projected to move to higher latitudes in unprecedented ways.

∼3.5 billion people (roughly 30% of the projected global population) would have to move to other areas if the global population were to stay distributed relative to temperature the same way it has been for the past millennia.

Strong climate mitigation (RCP2.6 instead of RCP8.5) would substantially reduce the geographical shift in the niche of humans and would reduce the theoretically needed movement to ∼1.5 billion people (∼13% of the projected global population.

Each degree of temperature rise above the current baseline roughly corresponds to one billion humans left outside the temperature niche.

Discussion

Why have humans remained concentrated so consistently in the same small part of the potential climate space? The full complex of mechanisms responsible for the patterns is obviously hard to unravel. The constancy of the core distribution of humans over millennia in the face of accumulating innovations is suggestive of a fundamental link to temperature. However, one could argue that the realized niche may merely reflect the ancient needs of agrarian production. Perhaps, people stayed and populations kept expanding in those places, even if the corresponding climate conditions had become irrelevant? Three lines of evidence suggest that this is unlikely, and that instead human thriving remains largely constrained to the observed realized temperature niche for causal reasons.

First, an estimated 50% of the global population depends on smallholder farming, and much of the energy input in such systems comes from physical work carried out by farmers, which can be strongly affected by extreme temperatures.

Second, high temperatures have strong impacts, affecting not only physical labor capacity but also mood, behavior, and mental health through heat exhaustion and effects on cognitive and psychological performance.

The third, and perhaps most striking, indication for causality behind the temperature optimum we find is that it coincides with the optimum for economic productivity found in a study (Burke 2015) of climate-related dynamics in 166 countries. To eliminate confounding effects of historical, cultural, and political differences, that study focused on the relation within countries between year-to-year differences in economic productivity and temperature anomalies. The ∼13 °C optimum in MAT they find holds globally across agricultural and nonagricultural activity in rich and poor countries. Thus, based on an entirely different set of data, that economic study independently points to the same temperature optimum we infer.