19 Technology

19.1 R&D in Development -China

China’s leaders embraced economic growth, but that growth has always been toward the telos of comprehensive national power. China’s young people may be increasingly ready to cash out and have some fun, but the leadership is just not there yet. They’ve got bigger fish to fry — they have to avenge the Century of Humiliation and claim China’s rightful place in the sun.

GaveKal Dragonomics’ Dan Wang:

I find it bizarre that the world has decided that consumer internet is the highest form of technology. It’s not obvious to me that apps like WeChat, Facebook, or Snap are doing the most important work pushing forward our technologically-accelerating civilization. To me, it’s entirely plausible that Facebook and Tencent might be net-negative for technological developments. The apps they develop offer fun, productivity-dragging distractions; and the companies pull smart kids from R&D-intensive fields like materials science or semiconductor manufacturing, into ad optimization and game development.

The internet companies in San Francisco and Beijing are highly skilled at business model innovation and leveraging network effects, not necessarily R&D and the creation of new IP….I wish we would drop the notion that China is leading in technology because it has a vibrant consumer internet. A large population of people who play games, buy household goods online, and order food delivery does not make a country a technological or scientific leader…These are fine companies, but in my view, the milestones of our technological civilization ought to be found in scientific and industrial achievements instead.

It’s become apparent in the last few months that the Chinese leadership has moved towards the view that hard tech is more valuable than products that take us more deeply into the digital world. Xi declared this year that while digitization is important, “we must recognize the fundamental importance of the real economy… and never deindustrialize.” This expression preceded the passage of securities and antitrust regulations, thus also pummeling finance, which along with tech make up the most glamorous sectors today.

In other words, the crackdown on China’s internet industry seems to be part of the country’s emerging national industrial policy. Instead of simply letting local governments throw resources at whatever they think will produce rapid growth (the strategy in the 90s and early 00s), China’s top leaders are now trying to direct the country’s industrial mix toward what they think will serve the nation as a whole?

And what do they think will serve the nation as a whole? My guess is: Power. Geopolitical and military power for the People’s Republic of China, relative to its rival nations.

If you’re going to fight a cold war or a hot war against the U.S. or Japan or India or whoever, you need a bunch of military hardware. That means you need materials, engines, fuel, engineering and design, and so on. You also need chips to run that hardware, because military tech is increasingly software-driven. And of course you need firmware as well. You’ll also need surveillance capability, for keeping an eye on your opponents, for any attempts you make to destabilize them, and for maintaining social control in case they try to destabilize you.

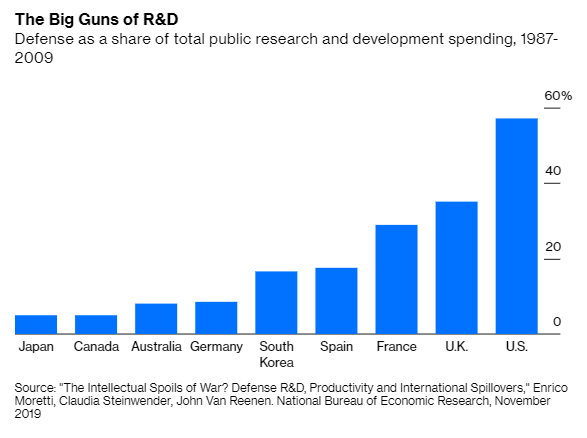

It’s easy for Americans to forget this now, but there was a time when “ability to win wars” was the driving goal of technological innovation. The NDRC and the OSRD were the driving force behind government sponsorship of research and technology in World War 2, and the NSF and DARPA grew out of this tradition. Defense spending has traditionally been a huge component of government research-spending in the U.S., and many of America’s most successful private-sector tech industries are in some way spinoffs of those defense-related efforts.

19.2 Automation

Robots

There is a threat to people’s jobs. But that threat is not the robots - it is company decisions that are driven by a broader economic and political system of corporate capitalism.

19.3 Infrastructure

Khalili

Apocalyptic Infrastructure

While we sometimes stand in awe of gargantuan infrastructures like ports and bridges, we hardly ever appreciate the aesthetics of water and sewer systems whose subterranean routes make them invisible, or even electricity lines, telecommunication masts and satellite dishes, which are visible but unremarkable because of their ubiquity. These basic utilities constitute the furniture of our everyday lives, and they often make themselves felt only when they break down, like when toxic water pours out of the tap or the electric grid goes down after a hurricane.

Climate change and its effects — erratic temperatures, stormy weather, rising seas — portend the destruction of both awesome and quotidian infrastructures, without many of which our lives would be diminished. Welcome to the age of apocalyptic infrastructure.

New infrastructural inventions have revolutionized production, trade, consumption and war. Irrigation made agriculture possible in inhospitable climates. Railways, canals, mines and shipyards facilitated the movement of goods and the working of capitalist commerce and propelled Europeans to colonize and displace indigenous people from distant lands.

The British built railways in their colonies in Africa and Asia. But especially in Africa, the rails lead to the sea from inland mines, sometimes entirely avoiding population centers, and when they were not used to extract raw resources, they were conduits for the movement of troops.

Even today, extractive industries in Africa, Latin America and Asia enrich a miniscule minority who often live abroad, while impoverishing and endangering many locals. Both the Suez and Panama canals were built with conscripted or unpaid, unfree labor and at the cost of thousands of lost lives. Later, governments wielded the potential construction of infrastructure as a reward or punishment for intransigent populations in the peripheries and borderlands. The infrastructures that made possible industrial agriculture and capital accumulation also led to dispossession and proletarianization on a mass scale in some places, starvation in others.

But infrastructure construction was also foundational to revolutionary and anticolonial movements. The French Revolution saw the emergence of new education, communication and transportation systems. Under Henri Christophe, emancipated Haiti began to develop a national school system, until France’s brutal demand for indemnification of former slavers mired the island country in debt for the next 150 years. The Russian Revolution of 1917 set the stage for the electrification and integration of the vast Eurasian expanse. In China, the Communist Revolution was followed by the construction of transportation, education, health and industrial infrastructures.

Environmental Effects

Across political divides, all infrastructures share one common feature: their detrimental environmental effects. Dams destroy riverine ecosystems and leach the soil. Cement factories and coal-powered electricity spew out pollution across the globe. Sewer lines pour into sensitive riparian and coastal biospheres. Oil fields and pipelines contaminate vast swathes of land, leaking into fragile water tables. Data centers produce carbon dioxide and heat on a monumental scale.

Finanicialization: New Asset Classes

Infrastructures have been seen as a foundational step toward the development of a capitalist economy and the pacification of revolutionary populations to boot. More recently, former U.S. Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson proposed “a new asset class comprised of things such as productive soils, crop pollination and watersheds,” further entrenching the financialization of the environment and of infrastructures themselves.

Redistributive Infrastructure

But what if infrastructure is designed, financed and adopted into the habits of everyday lives of its users in such a way that it is not a harbinger of apocalypse? I fear that thinking of infrastructures in a generalized and totalizing way, as always only girding the structures of capital accumulation, only ever destroying our ecosystem, only ever as death-dealing — also entrenches those same infrastructures by making them seem insurmountable. Such thinking would make it seem that the peculiarly capitalist modality of infrastructure today is the only possible way we can live with and alongside it. What if we began to imagine a new way of building what is needed that does not inexorably turn the oceans, the shores, the soil, the air we breathe and the water we drink into an asset class to be traded on markets?

The justification for the construction of infrastructures is frequently economic growth, so a significant step toward a more just infrastructural life would be to dethrone growth as the measure of social and political wellbeing.

The dilemma is how to provide a livable life and livelihood, health, education, basic utilities, clean air and clean water without hitching them to the zero-sum game of growth.

Infrastructures that would emerge out of an ideology of degrowth would incorporate a more redistributive, participatory and egalitarian ethos. And a strategy of degrowth would include ecological wellbeing as an immutable principle in all planning and use.

Infrastructures would have to be redistributive. They must not enrich some at the expense of others. The World Bank recommends public-private partnerships for the construction of roads and other transport infrastructures, but it does not grapple with the long-term costs to the public purse or the common expatriation of profits to global conglomerates. Even where the profits remain within the country, they often end up concentrated in the hands of the private investors who can foot the bill for the large-scale expenditures that infrastructures require, while the risks associated with badly planned and poorly constructed infrastructures are socialized.

19.4 Energy Transition

Tooze on Malm

Technology and Class Struggle In the mainstream that Malm is criticizing there are three predominant views of the coming of the steam-powered factory. Malthusian economic historians (most prominently Tony Wrigley and Ken Pomeranz) argue that by the late 18th century, the European economy was running out of fuel and found an answer to this functional imperative in the form of coal. For other writers, the mastery of steam power is simply the development of humanity’s long coevolution with combustion. Managing fire is part of what makes us human. Finally, one can see the advent of steam as first and foremost a technological achievement born out of the scientific revolution and the logic of discovery and enquiry.

Each of these narratives, in its own way, aligns fossil fuel revolution with necessity. For the Malthusians the industrial revolution follows from the imperative need to find ways of overcoming the scarcity of firewood and food. For others it follows from human nature and our drive to mastery. Or, finally, it follows the necessary logic of scientific development.

The problem, according to Malm, is that none of these plausible theories is actually empirically persuasive. Malm argues that through to the mid-nineteenth century, water power was a fully viable economic alternative - both abundant and cheap. To understand what is going on we have to go inside the factory to see how fossil fuels enter as the essential but hitherto unacknowledged complement to the struggle between capital and labour. What was ultimately decisive in Malm’s view was the question of control, or in Marxist terms real rather than formal subsumption. Ultimately, what shaped the technological choices of the British industrialists was the class struggle.

Mobilizing the stock of fossil energy layered under the ground was the weapon with which British capitalists fought back against the upsurge in unionism and Chartism in the 1830s and 1840s. Water was cheap and abundant, but unlike the power unleashed from coal, it could not be controlled. As Malm remarks, “If the autonomy of the working class is to be fought by a regiment of machinery, the prime mover – the field commander – had better be reliable.”[1]

Autonomy is the key word here. Though the basic insight of the role of coal is to be found in Marx’s Grundrisse, it was Italian Marxists of the so-called autonomist school, struggling in the 1960s and 1970s to make sense of the new abundance of Fordist mass production, who insisted on the fact that technology and class struggle were not separable. As Toni Negri, one of their leaders put it, the basic challenge facing the employer was to subjugate the autonomous potential or Potenza of human labour. The machine was the means for doing so. The classic separation of forces and relations of production was false. In fact the relations of production (as in class struggle) were inside the machinery itself. What Malm adds is the recognition that the driving force of that coercive synthesis is the mobilization of fossil fuels.

This isn’t just an imaginative theoretical and historical move. It grounds Malm’s skepticism towards the possibilities of reform today. If the relationship between non-renewable one-way exploitation of stocks of energy and the birth of capitalism is not accidental, if it is entangled in the most basic logic of surplus-value-generation, it will be far harder than is commonly imagined to dissociate capitalism from fossil fuels.

Ultimately, a system reliant on the unpredictable flows of natural energy, does not permit the same kind of comprehensive subordination enabled by the unlocking of stocks of coal, oil and gas. It is naïve to imagine that you can simply change the technology and leave the old relations of power and economy in place. In the limit, this would be imply that only comprehensive revolution or a truly coercive state apparatus can impose the energy transition we need.

Tooze (2021) Chartbook #50: Andreas Malm and ecological Leninism