4 Napoleonic Empire

Tooze

As magnetic as the figure of Napoleon may be, in focusing narrowly on the Emperor’s plans and ambitions, we underestimate the impact of the “Napoleonic era”, which was defined both by French action and the massive counter-acting forces that were mobilized against him.

Napoleon’s excessive ambition and success summoned up peripheral coalitions that after his defeat would dominate European affairs for much of the early 19th century. In the East, Russia emerged as the arbiter of continental power. The Tsar’s cossacks cantered through the streets of Paris in 1814. Russia would have a decisive voice in German affairs until Bismarck spied a window of opportunity to resolve the German question in the 1860s.

Offshore, the British Empire held Napoleon in check. Napoleon’s great victories in Germany in 1805-1807 followed on the decisive defeat of the French and Spanish navies at Trafalgar.

To fight Napoleon and bankroll his enemies, London mobilized an unprecedented financial war effort that may have extracted as much as 18 percent of GDP in tax, an astonishing figure for a country on a GDP per capita as modest as that of the UK in the early 1800s. At a rough estimate, the UK in 1800 had a GDP per capita of roughly $2500 in modern dollars. To devote 20 percent of that to a foreign war, was a huge mobilization.

And onerous as they were, Britain’s debts did not leave it bankrupt. With the gold standard restored by the 1820s, and conservative austerity imposed, London emerged from the long struggle against revolutionary France as the financial capital of the world.

Britain also commanded the highways of the oceans more than ever before. It was the Napoleonic wars that laid the foundations of UK naval supremacy.

By the 1820s the outlines of a new global economy were visible, a new “global condition” that was framed by the Britain’s global empire.

Tooze (2023) In the beginning was Napoleon

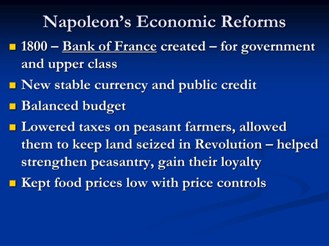

4.1 Economic Reforms

Roberts

Indeed, it is the economics of Bonaparte’s war against the reactionary monarchial powers of Britain, Austria, Prussia and Russia that is missing from Scott’s primitive biopic which concentrates on the battles, his personality and on his sexual relationship with Joséphine de Beauharnais, the daughter of a slave-owning sugar planter. Yes, individuals can affect history, but as Marx pointed out in his essay, The 18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte (when analysing the coming to absolute power of Napoleon’s nephew ‘Emperor’ Louis in 1852): “Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past.”

Napoleon started as a radical revolutionary supporting the Jacobin regime and ended up as an ‘emperor’ (much to the disgust of democrats like the composer Beethoven who in protest removed his dedication to Napoleon for one of his symphonies). Napoleon came to power as the defender of the republic, but he turned a war of defence into wars of conquest for an empire in Europe to compensate for the empire that had been lost in India, the Caribbean and North America in the latter part of the 18th century.

The term Bonapartism was coined to describe how one man can gain absolute power in a situation where the class forces are so balanced and unstable that the progressive class forces are unable to rule directly in the face of the opposition of reactionary class forces.

Performed the task of …. unchaining and setting up modern bourgeois society.

Created inside France the conditions under which alone free competition could be developed, parceled landed property exploited and the unchained industrial productive power of the nation employed; and beyond the French borders he everywhere swept the feudal institutions away, so far as was necessary to furnish bourgeois society in France with a suitable up-to-date environment on the European Continent.

One man can make history but only within the conditions given. It was the economic conditions and balance of forces that decided the ‘Napoleonic wars’. Napoleon won many battles, but he still lost the war. Why? The evidence reveals that France just did not have the resources of manpower, arms and, above all, finance to wage a long war against the combined powers of the absolute monarchies backed by the firepower and wealth of a rising hegemonic Britain.

To sustain war depends on two measures: the economic resources available to fund war and the ability to get armaments supplied and fit men to the battlefield. From 1789 to 1815, France faced seven opposing Coalitions and managed to defeat six. As one analyst put it: “this feat is often attributed to the tactical and strategic thinking of Napoleon Bonaparte. However, the country was eventually defeated under the pressure from the combined superior economic, demographic, industrial strengths of the Allies.”

The French revolutionary republic after 1789 was immediately faced with a reactionary counter-revolution from the Royalists at home and foreign invasion from abroad. And it had no money to fund the defence of the republic. The Jacobin leaders hoped that the confiscation of Church wealth and royal properties would deliver. But what was raised was just not enough to build a fighting successful army and meet the social needs of a starving population. So the revolutionary government printed money – indeed there was already private printing of money that was out of their control. The money supply rocketed and so did inflation.

In 1793, under the Jacobin government, total money in circulation was valued at almost 3 billion francs, more than double the original sum raised from confiscations. The starving population looted shops for clothes and food. The government then paid out social benefits to restore stability. By 1795, total money supply increased to 4.4 billion francs and the franc exchange rate with the British pound plummeted by 45%. By the point of the counter-revolutionary removal of the Jacobin leadership and the establishment of the Directory, the money supply had multiplied to 20 billion francs, on top of which the government has issued bonds for another 50 billion.~

But it was not all disaster, contrary to the views of historians today. The French republican economy was actually beginning to motor. Coal production doubled between 1794 and 1800 when Napoleon took over. Iron production rose 50% and salt by even more. These were key products for a budding industrial and urbanising economy. This industrial production was driven by the needs of the war economy. The French defence industry was developing fast. Above all, agricultural and food production recovered – if not enough to stop food prices rising. While Britain’s war economy managed a 25% rise in agricultural production in the first decade of the 1800s, France under Napoleon raised agro production by 500% – but it started from such a low level, even that increase was not enough to meet demands of the army and the civil population’s needs.

The right-wing Directory eventually gave way to a Bonapartist coup in 1799-1800, giving Napoleon supreme powers to ‘save the revolution’ and defeat royalist reaction at home and abroad. Like a good ‘bonapartist’, Napoleon balanced between the class forces of bourgeois and merchants and the ‘masses’ of peasantry and artisans (sans culottes). Formerly a ‘fellow traveller’ of Robespierre’s Jacobins, he came to power preaching prosperity for the masses over the interests of the big merchants and the aristocracy and ended up as an emperor of Europe.

Napoleon always stood on the side of the capitalist mode of production against that of feudalism and the ancient regime, despite declaring himself emperor in 1805. On the other hand, he was strongly opposed to any ‘socialistic’ alternatives that some more radical forces among the Jacobins proposed.

Before 1789 the manual worker laboured from 20-39 working days per year to pay his taxes; after 1800, from six to 19 days and “through the almost complete exemption [from taxes] of those who have no property, the burden of direct taxation now falls almost entirely on those who own property.”

As Marx put it in the 18th Brumaire: “After the first Revolution had transformed the semi-feudal peasants into freeholders, Napoleon confirmed and regulated the conditions in which they could exploit undisturbed the soil of France which they had only just acquired, and could slake their youthful passion for property ….Under Napoleon the fragmentation of the land in the countryside supplemented free competition and the beginning of big industry in the towns. The peasant class was the ubiquitous protest against the recently overthrown landed aristocracy. The roots that small-holding property struck in French soil deprived feudalism of all nourishment. The landmarks of this property formed the natural fortification of the bourgeoisie against any surprise attack by its old overlords.”

While the reactionary monarchies financed their war by printing money and relying on the huge empire war chests of the British treasury, Napoleon’s France had to rely on domestic taxation, which was never enough, and on booty from conquests in the Netherlands, Italy, Austria and Prussia. At home, Napoleon sorted out the finances. Money printing was ended and inflation receded. And up to at least 1812, war booty usually brought in more than the battles cost. The defeated countries were charged high fees.

France’s economy was still inefficient when compared to that of Britain. French industry could not meet the demands of the prolonged war that Napoleon initiated and this forced the Grand Armée to rely heavily on war booty. The irony is that it was Britain that printed money and issued bonds to pay for the war. But Britain could do that because bond holders could be confident that after the war revenues from Britain’s industrialization and huge colonial empire would easily service such debt. France had no such economic credibility.

The reality was that overall French finances were much lower compared to that of Britain. In 1805, the French budget was just £27m, whereas the British was £76 million. In 1813, the French expenditure rose to £46m but the British budget reached £109 million. In spite of the continued exploitation of occupied countries, the French government debt rose five times between 1809 and 1813.

In 1800, per capita GDP in England was twice as large as France.

There was an immense imbalance in economic power between Britain and France. France may have occupied Europe, but Britain had the colonies of America, Canada, Africa, India, and Asia behind it. Britain, based on its international trade, could mobilize more economic resources, raw materials and labour than France. In a prolonged war, Britain could survive longer and better than France.