3 Auto Industry

Smith

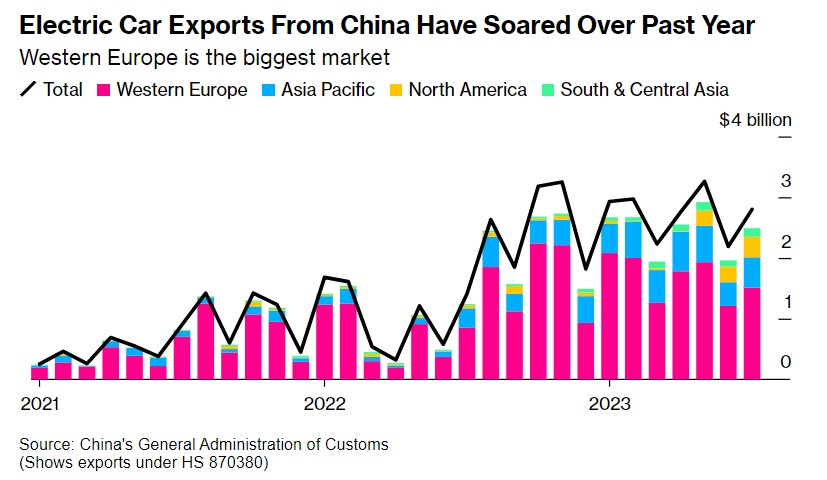

China is flooding Europe with electric cars. Over the past two years, China has gone from an also-ran in the auto industry to the world’s biggest car exporter. EVs are a huge chunk of those exports, and most of China’s EV sales go to Europe.

Some forecasts say that by 2025, about 15% of EVs bought in Europe will be made in China — some by Western automakers like Tesla and Volkswagen, some by Chinese companies like BYD.

It’s very easy to understand why this is happening. China massively subsidizes the production of electric vehicles, and Europe massively subsidizes the consumption of electric vehicles. When that happens, any Econ 101 model can easily predict the outcome — China will produce a lot of EVs that are sold in Europe.

In fact, this basic dynamic was present even before the recent export surge. Usually, most cars are made close to where they’re sold. But even in 2021, Europe was buying more EVs than it was making.

China pays manufacturers a subsidy worth more than $1400 per EV they produce, provides EV companies with cheap land and financing, and heavily subsidizes R&D in the sector. Both China and Europe pay people to buy EVs, and their governments buy EVs directly. But China subsidizes local production a lot more than Europe.

That’s one reason for China’s export dominance, but not the only one. Another is that China controls nearly the entire supply chain for EV batteries, except for the initial mining.

Losing the car industry could thus push Europe further along the path to deindustrialization. Cheap Chinese EVs are a boon to European consumers, and they help speed the green transition and reduce carbon emissions. But the competition also threatens to put a bunch of European workers out of a job — 7% of the region’s workforce work in the automotive sector. Traditionally, Europe has been much more concerned than the U.S. about protecting its industries from foreign competition; the EV spat with China will be a test of whether this is still the case, or whether Europe has embraced more of a “neoliberal” approach to trade.

But there could also be a national security angle here too. The Ukraine war is stalemated, and promises to be a long slog, even as U.S. domestic politics puts American support for Ukraine in jeopardy. That means that the job of supporting Ukraine’s continued independence will fall to Europe; and if Ukraine does fall, Europe will still be on the hook, since Putin will then turn his eyes to Poland and the Baltics. So Europe will need to match Russian war production, in areas like shells, missiles, artillery, air defense, drones, and armored vehicles. A domestic auto industry gives Europe much more ability to repurpose production lines and ramp up defense production when needed. If the auto industry flees to China, Europe will be that much more vulnerable to Russia. In fact, this is one reason the auto industry is so globally distributed today; during and after World War 2, lots of countries decided they needed car industries in order to maintain strong militaries.

In order to address these issues, Europe would need more than tariffs. It would need an equivalent of the U.S.’ Inflation Reduction Act — a major program of production subsidies, not just for EVs themselves but for the batteries and the mineral processing facilities necessary to make them.